Decoding the language of Gilded-Age social signals

From the archives

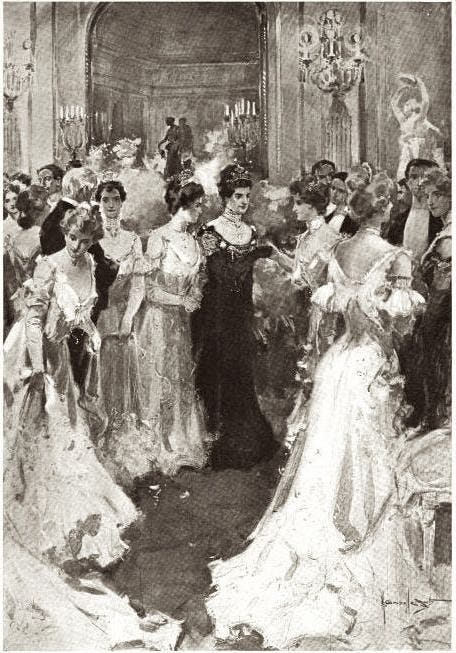

In the opulent parlours, glittering ballrooms, and manicured gardens of the Gilded Age elite, words were often the least important part of a conversation.

Society functioned as a grand stage for the British and American aristocracy, where appearance, gesture, and nuance held as much significance as any carefully spoken remark.

The strict etiquette of the era made it essential for the well-bred to master a complex web of unspoken social cues. From the subtle language of fans to the choreography of ball invitations and the politics of calling cards, they needed to know several hidden languages if they had any hope of survival.

And while codes existed on both sides of the Atlantic, their character and importance often diverged in fascinating ways, leaving many a newly arrived Dollar Princess bewildered by the nuances of British high society.

A world of unwritten rules

The Gilded Age was a time of immense wealth and strict social categorisation.

While fortunes were made in industry, finance and railroads in the United States, Britain’s aristocracy remained rooted in hereditary privilege, ancient titles and landed estates. Despite these differences, however, both cultures upheld highly codified etiquette systems to differentiate themselves from the common masses.

In public and private gatherings, a misplaced glance, an ill-timed visit, or the wrong seating arrangement at a dinner party could spark scandal…or worse: social exile.

To endure this unforgiving landscape, one had to master the most delicate of arts: observation and implication.

The subtleties of behaviour (who one spoke to, the depth of a curtsy, or whether a gentleman removed his gloves before a handshake) conveyed entire conversations in themselves.

Courtship and covert conversations

In courtship rituals, social cues were particularly vital, and directness was discouraged. In fact, Gilded Age aristocrats employed myriad non-verbal systems.

In Britain, courtship was overseen with rigid formality. Chaperones accompanied unmarried women, and public displays of affection were scandalous. Instead, a young lady might indicate her interest by ‘accidentally’ dropping a handkerchief or accepting a specific dance, typically the final waltz of the evening, which was reserved only for suitors of the most serious intent.

In America, the newly wealthy class emulated Old World customs, but they also often embraced them with more exuberance.

Lavish balls, like those thrown by New York’s Astors or Vanderbilts, became the settings for social performances. Young women were still carefully managed, but American hostesses had a reputation for being bolder in arranging matches and flaunting status.

Courtship rituals like the presentation of calling cards or carriage rides through Central Park provided carefully orchestrated opportunities for flirtation within socially approved boundaries.

Source: Caroline Astor and her guests, illustration, 1902. Author unknown. Via Wikimedia Commons.

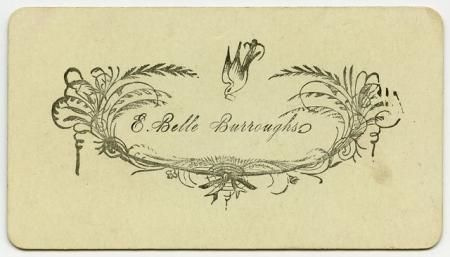

Calling Cards: The first social media

One of the most universally observed customs of the Gilded Age was the use of visiting, or calling, cards. Far more than a simple introduction, these cards were laden with meaning based on size, paper quality, typography, and presentation.

When making a social visit, the middle and upper classes would offer a calling card to the butler of the house, who, leaving the visitor to wait, would present it to the recipient on a silver tray, announcing their guest's arrival.

Subtle alterations in the card’s presentation conveyed specific messages:

A turned-down corner indicated a personal visit rather than merely sending a servant.

A card left with the name underlined expressed congratulations.

A black border signified mourning.

In Britain, the ritual was even more precise, with entire books dedicated to the etiquette of calling card exchanges. For example, one would never presume to leave a calling card for a Duchess unless expressly invited to do so…

In America, where new wealth often disrupted traditional hierarchies, cards served as a tool for asserting one’s place in society. An invitation to Mrs. Caroline Astor’s drawing room was the pinnacle of acceptance, making it an ambitious social climber’s most coveted possession.

Source: Example of a calling card. Author unknown. American Antiquarian Society.

Seating charts and social rankings

Whether at British country houses or American society dinners, where one was seated spoke volumes. In Britain, centuries of aristocratic protocol determined proximity to the host, with precedence given to title, gender, and age.

In America, however, where fortunes rose and fell overnight, seating was strategically utilised to forge alliances and flatter valuable guests.

A prominent position near Mrs. Astor or Mrs. Vanderbilt might indicate a family’s new status among New York’s Four Hundred—the unofficial list of society’s most exclusive members.

Every rose has its thorn

Even a simple bouquet could convey rivalry, admiration, passion or disdain…all without the stroke of a pen.

Drawn from the Victorian tradition of floriography, the British elite assigned specific meanings to different blooms. Red roses told of passionate affection, white camellias expressed admiration, and a sprig of heliotrope hinted at eternal devotion.

At society events, debutantes carried small, deliberate posies, their flowers carefully selected to send subtle signals to would-be suitors and female rivals alike.

The American elite enthusiastically embraced the custom, combining their ostentatious tastes with conservative European traditions to produce lavish floral displays laden with coded messages. Wealthy hostesses like Alva Vanderbilt and Caroline Astor were famed for their opulent arrangements, where no bloom was selected without purpose.

Etiquette manuals and floriography guides such as The Language and Poetry of Flowers by Frances S. Osgood were indispensable to society women seeking to navigate this delicate, fragrant form of conversation.

Fashion as a signal

Beyond style, clothing in the Gilded Age was a complex indication of where one sat in the pecking order.

In both Britain and America, the cut of a gentleman’s evening coat or daring exposure of a lady’s décolletage at a ball conveyed messages about status, wealth, and moral character.

British aristocracy adhered to a more conservative dress code, which emphasised tradition. Meanwhile, American society women became known for their ostentation.

Designers like Charles Frederick Worth of Paris found eager clients among America’s nouveaux riche, who favoured embellished gowns and towering tiaras for society balls. A Worth gown was a statement of both financial might and cultural cachet.

Source: Ball gown, House of Worth, ca. 1872. The Met Museum.

Culture Clash: The heiress abroad

Nowhere were the differences in social cues more keenly felt than by the American heiresses who married into the British aristocracy during the Gilded Age.

The young women who crossed the Atlantic were raised amidst the comparative informality and flamboyance of American high society, and so the rigid etiquette of Britain’s stately homes could be both bewildering and oppressive.

In New York or Newport, a well-placed flirtation or a bold fashion statement could catapult one into favour. In England, the same behaviour might be viewed as shamefully improper.

Jennie Jerome ( Lady Randolph Spencer-Churchill, the vibrant mother of Winston Churchill) famously ruffled feathers in British society with her spirited independence and American manners.

Source: Lady Randolph Spencer-Churchill, photograph by José María Mora, 1880s. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Consuelo Vanderbilt, one of the era’s most famous heiresses, married the 9th Duke of Marlborough at the insistence of her formidable mother, Alva Vanderbilt.

Though Consuelo brought a $2.5 million dowry (equivalent to around $80 million today), she struggled to adapt to Blenheim Palace’s ancient protocols and the rigid formality of the British upper class. In her memoirs, The Glitter and the Gold, she recounted feeling like a pawn in a dynastic game, stifled by expectations she found completely alien.

Source: The Duchess of Marlborough, 1900–1905. Author unknown. Via Wikimedia Commons.

As Gail MacColl argued in her 1952 book, To Marry an English Lord, many American brides struggled with the labyrinthine etiquette of country house weekends, elaborate seating plans, and unyielding class structures.

The British emphasis on reserve and understatement often frustrated these women, who were accustomed to commanding attention and orchestrating grand social manoeuvres back home.

Reading between the lines

The social cues of the Gilded Age formed an unspoken language as intricate as any verbal dialect.

From calling cards to carefully orchestrated courtship rituals, the aristocracies of Britain and America turned everyday gestures into performances heavy with meaning.

Today, these customs offer a captivating glimpse into the values, rivalries, and ambitions of a bygone world—one where a flick of a fan, the shape of a bloom, or the folded corner of a calling card could shape fortunes on both sides of the Atlantic.

This was wonderful! It's so important to remember all of the points you've made, as it helps us get a more accurate picture of the time. Everything was intentional. I always wonder how nervous the Heiresses must have been heading into British society.

Your words ring true in today's society of emails and voice mails. I still use my calling cards and and write thank you notes and notes in general...... hopefully an old tradition will be "new" again.....one can hope!