Powder and Perfume:

Beauty Secrets of the Gilded Age Elite

During the Gilded Age, beauty was both an asset and a weapon.

The period, roughly spanning 1870 to 1910, was one of opulence and excess for both America’s nouveau riche and Britain’s aristocracy, where heiresses, duchesses, and socialites not only jostled for position on the social register but also for the most luminous complexion, fashionable scent, and striking ensemble, too.

Beauty secrets were highly prized on both sides of the Atlantic, as new trends and products crossed oceans as swiftly as steamships could carry them.

But the subject is more than skin deep, with the beauty rituals revealing much about the era’s social anxieties, its flirtation with modernity, and the fascinating women who fought to leave their mark in a time where their only route to power was through wealth and family name.

So, let’s step inside the boudoirs of history and decode the make-up, fragrances, and cosmetics of the Gilded Age, and the colourful women who wielded them.

Complexion Obsession: Pale, porcelain skin

A flawless, pale complexion was the ultimate marker of aristocratic refinement.

In the 1800s, tanned skin suggested manual labour and lower status, so women went to extraordinary lengths to preserve their fairness.

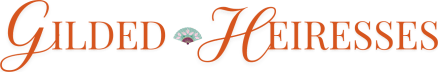

Aside from parasols, gloves, and veils, face creams, rice powders, and whitening lotions were commonly used, often containing problematic ingredients like lead, mercury, and arsenic.

One such formula, Dr. Rose’s Arsenic Complexion Wafers by Sears & Roebuck, was designed to be ‘perfectly harmless’ when used correctly (i.e. delicately nibbled on throughout the day by men and, mostly, women who sought an unblemished, milky pallor).

Source: Illustration of Dr. Rose’s Arsenic Complexion Wafers, artist unknown, c. 1800s, via History Myths Debunked.

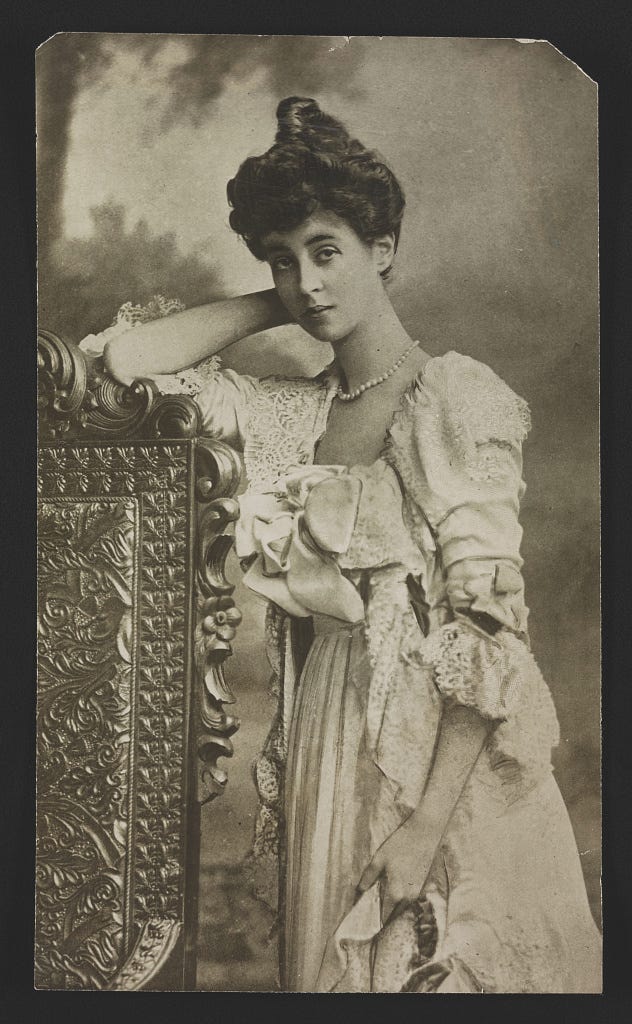

Beauty Icon: Lillie Langtry

Known as the “Jersey Lily,” actress and society beauty Lillie Langtry was famed for her alabaster skin. So renowned were her looks and vivacious character that she even caught the eye of Edward, Prince of Wales, and became one of the most high-profile mistresses of the era.

While Lily’s exact skincare routine isn’t known (perhaps it was secretly guarded?), many elite women sought to achieve a pale complexion through a strict regimen of rosewater spritzes, cold cream masks, and a total avoidance of ‘unnecessary’ sunlight.

Source: Photograph of Lillie Langtry, c. 1890, W. & D. Downey. Via Getty Images.

The discreet art of Gilded Age make-up

Despite the demand for flawlessness, cosmetics were a double-edged sword.

Heavy make-up was associated with actresses or women of ill repute, so respectable ladies favoured subtle enhancements.

Pale rice powders, discreet lip stains made from carmine (a red colouring derived from crushed insects still widely used in make-up today), and light eyebrow and eyelash darkeners were sequestered in elegant vanity sets, away from prying eyes.

The use of cosmetics was a transatlantic convention. Whether British ladies-in-waiting or New York debutantes, women everywhere pinched their cheeks and dabbed their homemade rouges.

For American women, however, particularly those in cosmopolitan centres like New York and Newport, the yoke of tradition was loose enough to allow for bolder cosmetic choices than their British counterparts, who remained largely tied to notions of restrained and ‘natural’ beauty.

Source: Preparing for the Dance by Joseph Caraud, 1821-1905. Via Bonhams.

Beauty Icon: Jennie Jerome (Lady Randolph Churchill)

The American mother of Winston Churchill, born Jennie Jerome, was a social whirlwind known for her dramatic dark eyes and perfectly coiffed hair.

Many women like Jennie had a make-up arsenal including homemade rouge mixed with beet juice for a natural flush and dabs of lip salve tinted with crushed rose petals. The more daring may have even used kohl to rim their eyes in an attempt to stand out in a sea of fair faces.

Source: Painting of Jennie Jerome by John Singer Sargent, 1889. Via The Standard.

Signature Scents: Gilded Age fragrances

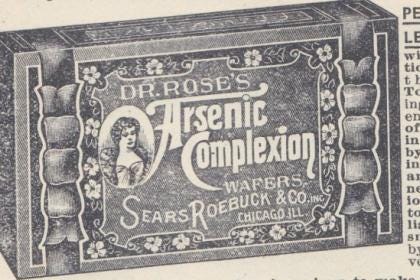

Fragrance was essential to a Gilded Age lady’s toilette, with richly scented perfumes, colognes, and floral waters indispensable for masking the odours of coal fires and un-air-conditioned ballrooms.

French perfumers like Guerlain and Houbigant dominated aristocratic dressing tables in Britain and America, with fashionable women eagerly sending for the latest Parisian releases.

Source: Photograph of Jicky by Guerlain, the world’s oldest continuously produced perfume. Photographer unknown. Via Proantic.

Though tastes overlapped, British society tended to favour lighter, single-note florals such as violet or lavender for daytime, while American socialites embraced more daring blends, including musks and orientals.

The influence of European perfumes on American society eventually led to an influx of home-grown perfumeries, typically utilising European names to capitalise on the association with luxury. One such example was that of E.W. Hoyt of Lowell, who christened his first fragrance ‘Hoyt’s German Cologne’, despite having zero Germanic heritage.

Beauty Icon: Consuelo Vanderbilt

Consuelo Vanderbilt, the American heiress who married the Duke of Marlborough, was as celebrated for her elegance as for her fragrance preferences.

Many ladies like Consuelo favoured delicate floral scents, particularly violet water, which symbolised modesty and refinement at the time. Their travelling cases would have contained glass bottles filled with imported French perfumes and lavender sachets.

Source: illustration of Consuelo Vanderbilt, c. 1903, by Paul César Helleu. Via Wikipedia.

Haircare Rituals: Tresses of the Gilded Age

Hair was a crowning glory in the 1800s. Elaborate updos, pompadours, and cascades of curls required meticulous care.

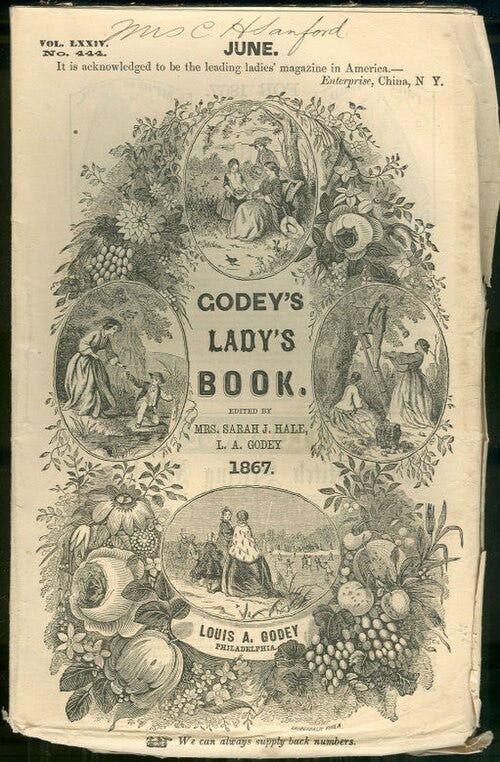

Hot irons, pomades, and floral hair oils were everyday essentials, and like cosmetics and perfume, haircare trends crossed easily between Britain and America via illustrated fashion magazines such as The Queen and Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Published between 1830 and 1896, the American journal was the most widely circulated publication before the Civil War and contained light, non-political content (from sheet music to poetry and, of course, fashion and beauty) deemed suitable for its audience of elite women.

Source: Picture of the cover of Godey’s Lady’s Book from June 1867. Via Wikipedia.

For both the British and American elite, elaborate hairstyles, often incorporating braids, twists, loops, and buns (such as the chignon style still seen today), were commonplace, with hair gathered up from the nape to emphasise the neck and shoulders. As the era progressed, artfully unkempt, voluminous hairstyles, such as the famous ‘Gibson Girl‘, became the ‘do du jour.

Source: Illustration of a woman sporting the Gibson Girl hairstyle by Charles Dana Gibson, circa 1891. Via Wikimedia Commons.

When it came to hair accessories, however, the difference in taste between the two nations was more pronounced. The British aristocracy opted for ribbons and flowers in the spring and summer, and silk alternatives in the colder months, which was a symbol of the reserved femininity of the time.

Meanwhile, high-class American women favoured bold accessories, from diamond tiaras to feathers, bows and elaborate headpieces designed to draw a second glance.

Beauty Icon: Alva Vanderbilt Belmont

Alva, a noted suffragist and socialite, was famed for her extravagant hair ornaments and glossy, dark hair. Her towering coiffures, often adorned with combs and lavish headpieces, soon became a signature of her public appearances.

Source: Photograph of Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, date unknown. Via National Park Service.

Beauty as social advancement

For Gilded-Age women, beauty was far more than mere vanity…it was currency.

In a world where the value of high-class women was first and foremost rooted in their wealth, breeding and obedience (to varying degrees between Britain and America), beauty allowed women to secure good matches, illicit admiration, and (most notably) wield influence.

Through these carefully orchestrated rituals, the women of the Gilded Age became trendsetters of fashion, hairstyles and make-up. Beauty was then, as it remains today, a form of self-expression for a demographic with limited access to higher education and independent careers.

And though the precise shades and scents might differ, the fundamental ideals of beauty (fair skin, glossy hair, delicate fragrance) transcended national boundaries.

Today, their meticulously curated looks remind us that while beauty standards may shift, the allure of a perfectly powdered cheek or a heady floral perfume remains eternal.

It’s interesting how many of the professional beauties are more of what we would call handsome women, rather than beautiful.

PS, the picture of Alva is actually of Consuelo.

Right up my alley with these topics 😉