The 400 of the Gilded Age

New York’s velvet rope, and announcement from me!

The Gilded Age backdrop

The closing decades of the nineteenth century in America were marked by dazzling opulence and startling inequality. The Gilded Age, as Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner dubbed it, was an era of glittering wealth overlaying deep social divides.

New York City was its stage: brownstone mansions, opera houses, and marble ballrooms served as both playground and battlefield for those intent on displaying their fortunes.

It was a corner of the world where sudden millionaires and fragile reputations, and status was not simply inherited. No, it was carefully curated, negotiated, and policed.

And no one symbolised that policing more than Ward McAllister and his fabled “400.”

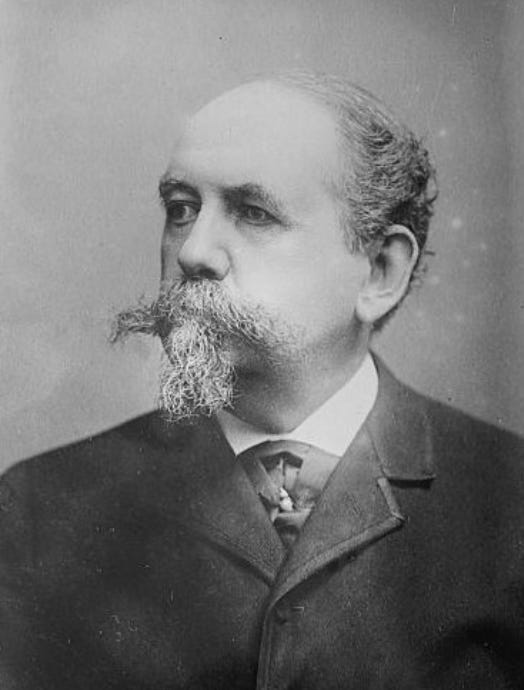

Who was Ward McAllister?

Ward McAllister was not a titan of industry, nor an heir to old money. He was a lawyer with Southern roots who reinvented himself as a social commentator and gatekeeper of taste.

With a keen sense of performance, McAllister positioned himself as the interpreter of elite society. As someone who could, with a flourish of words, define who belonged and who did not.

His pronouncements on etiquette, dining, and manners filled newspaper columns. But his most enduring legacy was a number: 400.

Why 400?

According to McAllister, there were only four hundred “truly fashionable” people in New York.

But that figure was not plucked from thin air. It was based on the size of Mrs. Caroline Astor’s ballroom, the most prestigious social venue in the city.

If Mrs. Astor could only host 400 at her grand Fifth Avenue mansion, then 400 became the magical limit of acceptance.

This turned a guest list into a cultural boundary line.

If your name appeared, you had ascended to the apex of New York society. If it did not, no amount of wealth or ambition could fully bridge the gap.

Mrs. Astor’s ballroom

Caroline Astor, the so-called “queen of New York society,” was the true power behind the 400.

Her approval was the coin of the realm. Though McAllister gave the number its publicity, it was Mrs. Astor who decided which names made the cut.

Her ballroom was less a space for dancing than a theatre of legitimacy. To be invited was to have one’s place in the social order confirmed.

To be excluded was a statement: your fortune, however vast, did not guarantee refinement, pedigree, or acceptance.

Old money vs. new money

The 400 was only partially a party guest list. More importantly, it was a symbolic barrier between old money and new.

The industrial fortunes of the Vanderbilts, Goulds, and Harrimans were remaking the American landscape, but the established families of Knickerbocker New York were wary of dilution.

The list, in effect, became a means of controlling the pace at which new wealth could enter the hallowed halls of society.

Yet, paradoxically, the allure of the 400 only grew.

Newspapers printed speculative lists of who was “in” and who was “out.” Ambitious families spent fortunes on opera boxes, country estates, and Paris gowns, all in hopes of climbing the social ladder.

The myth and its legacy

The precise roster of the 400 was never published in full, though fragments circulated in gossip columns.

Its power lay less in accuracy than in aura. To speak of the 400 was to evoke exclusivity, aspiration, and the tantalising drama of who was deemed worthy.

Over time, the number itself took on mythic resonance. It stood for more than the capacity of a ballroom. It stood for the human hunger to belong to an inner circle.

What the 400 reveals

The story of the 400 is, at heart, a story about boundaries. It illustrates how wealth alone is rarely enough; belonging depends on recognition by those who already hold power.

It also reflects a broader paradox of American life: in a country founded on ideals of democracy and openness, exclusivity has always retained a magnetic pull.

Even today, the notion of “the 400” lingers as shorthand for the elite, a reminder that social circles are never just about numbers.

They are about the lines we draw, the doors we close, and the endless human dance between inclusion and exclusion.

Our very own 400

I have a larger vision for this publication. Gilded Heiresses may have started on my original website as a side project while I worked on my Master’s dissertation—a place for me to write into all that I was learning about the era and about the women who crossed the Atlantic to marry into British aristocracy at the time.

But it’s now become so much more.

I’ve brought this project over to Substack in hopes to expand my research and therefore expand the historical accounts of our Gilded heiresses.

Starting at Mapperton, where I’m constantly discovering new, primary material relating to the era and its people, and on to distant archives, established scholars, and research trips to important sites…your subscriptions here help to fund it all.

Tomorrow, I’m launching the paid tiers, and I do hope that you’ll join me.

And, there’s something very special (to do with The 400) launching as well.

If you’re interested and able, keep an eye out tomorrow for how you can sign up to a paid subscription and help fund further research and restoration.

Xx Julie

Julie / my relative painted 4 prominent “400” families in miniatures - I have the history and images - would love to connect! Please look at kathleenlangone.com ! On Instagram - @phihpod

Julie,

You do have a familial tie to 3 of The 400 through Alberta. Alberta’s stepfather Francis Howard Leggett (my 2nd great granduncle) was a 2nd cousin to Anson Phelps Stokes (and his wife Helen (Phelps) Stokes) and his sister Olivia Egleston Phelps Stokes. Francis, Anson, and Olivia share a great grandfather William Stokes (1738-1786 England), woolen merchant and friend of the Countess of Huntingdon. Check out the Wikipedia pages of Anson and Olivia Stokes.

Fun fact: the actor Kevin Bacon is also a descendant William Stokes.