The Art of the Gilded Age dinner Party:

Menus, manners, and mistakes

A feast fit for the elite

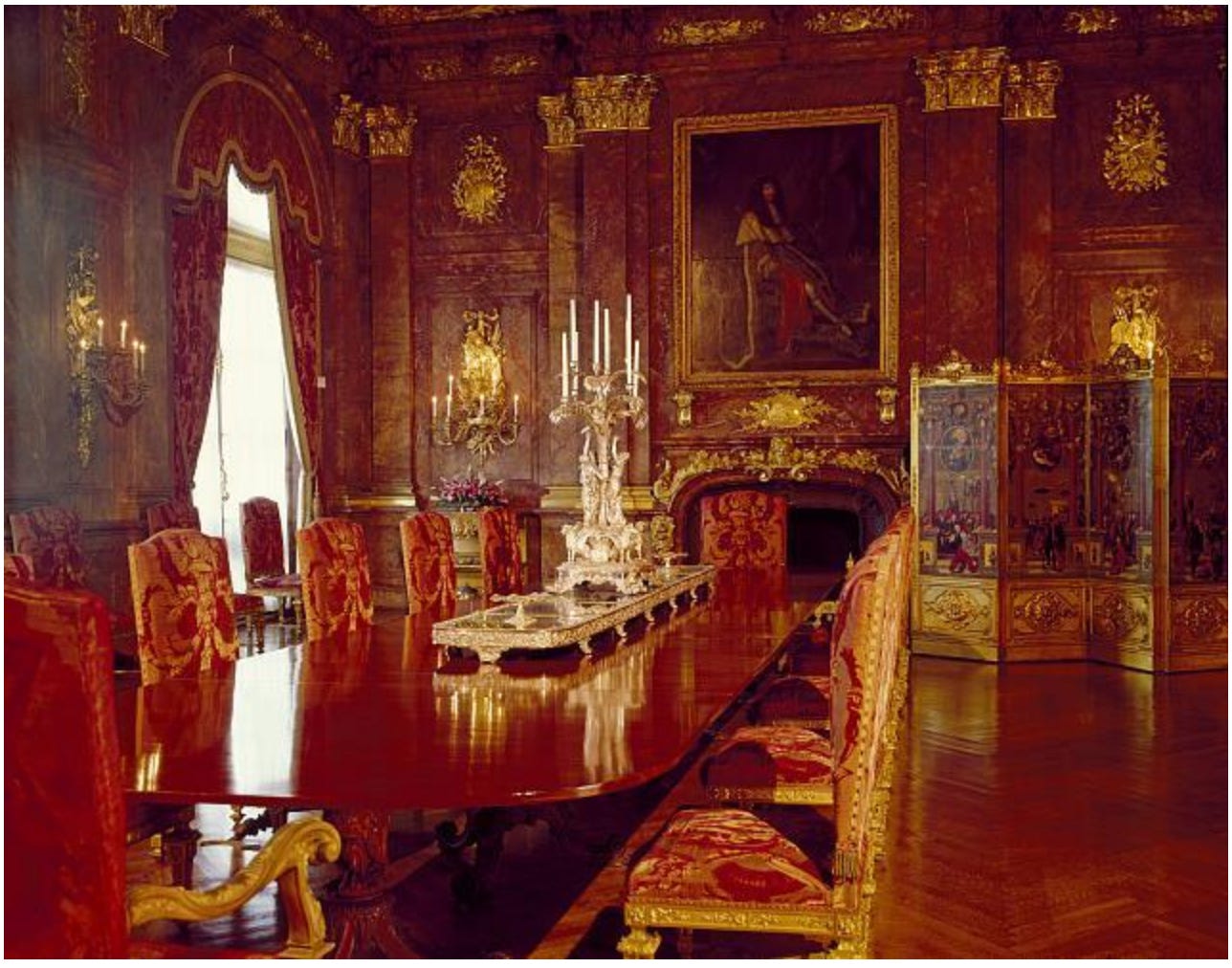

A Gilded Age dinner party would have had a glittering chandelier dripping with crystals, casting a golden glow over an impossibly long dining table.

(Downton Abbey, Carnival Films/MASTERPIECE)

The finest porcelain and crystal glassware would have sparkled under candlelight.

A butler would move soundlessly, refilling wine glasses with a perfectly aged claret.

The table would have been set with precision, the menu nothing short of a masterpiece, and everyone would have been on their best behaviour, because in the Gilded Age, one wrong move at a dinner party could spell social disaster.

If there is one thing British aristocrats knew how to do during this time period, it was how to entertain.

A formal dinner was not simply a meal; it was a carefully orchestrated display of wealth, status, and social finesse. Everything from the seating arrangement to the way a guest held their fork was a reflection of their breeding.

Dinner parties were more than a social event.

They were an opportunity to reinforce social hierarchies, cement political alliances, and showcase the host’s financial and cultural superiority. Guests were expected to navigate these occasions with absolute grace, knowing that a misplaced remark or a breach of etiquette could have lasting social consequences.

So let’s look at the anatomy of such an event, including what could go wrong!

The structure of a Gilded Age dinner party

The perfect Gilded Age dinner followed a strict sequence, unfolding like a theatrical performance with three distinct acts:

The arrival and aperitifs, where guests were welcomed and socialised before dinner.

The dinner itself, a carefully choreographed series of courses, served with appropriate wines.

The post-dinner rituals, where men and women separated for an hour before reuniting for final conversation and entertainment.

(Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress. Marble House, Rhode Island)

The arrival and the drawing room

A guest’s punctuality was paramount.

Arriving too early was inconsiderate, while arriving late could be a social catastrophe.

Upon arrival, guests were ushered into the drawing room, where the host and hostess formally welcomed them.

Drinks such as sherry, claret, or Champagne were served while guests engaged in polite conversation.

This was a crucial moment for social positioning.

Guests used this time to observe the room, assess the importance of their fellow attendees, and secure the best conversation partners for dinner.

Young women seeking advantageous marriages used this opportunity to impress potential suitors, while ambitious social climbers sought to endear themselves to powerful aristocrats.

After an appropriate amount of time, the host would signal the transition to dinner, and the guests would process into the dining room in order of rank, with the most important lady on the host’s arm and the most important gentleman on the hostess’s.

The dinner and the menu

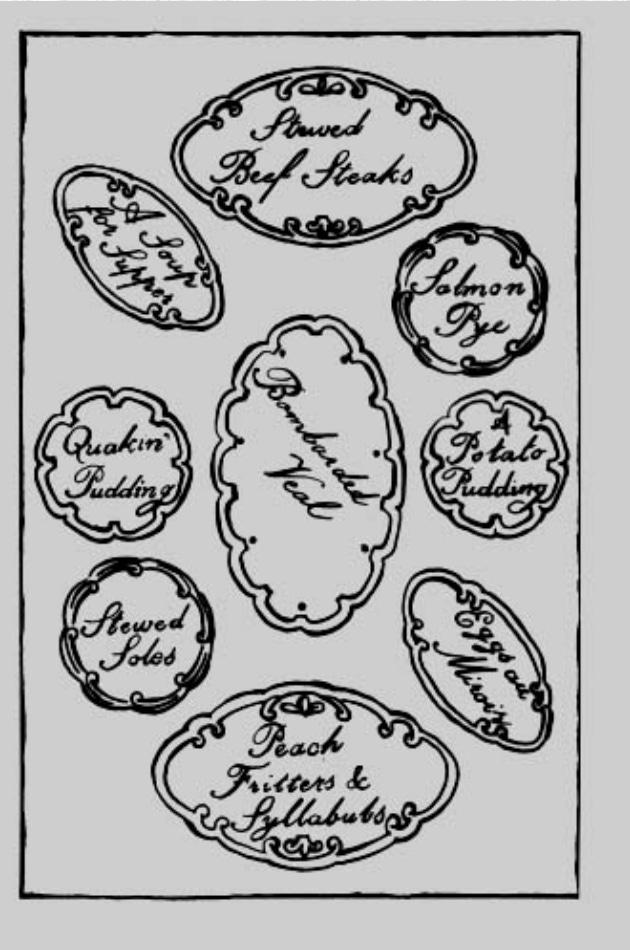

The dinner was the centrepiece of the evening, and the menu reflected the household’s wealth and refinement.

British aristocrats favoured a combination of French cuisine and traditional British game dishes, with multiple courses and wine pairings.

(From The Jane Austen Cookbook, pg 15)

A typical Gilded Age dinner party had anywhere from six to twelve courses.

A sample menu might include:

First course: oysters on the half shell with mignonette sauce

Second course: consommé à la Royale, a clear beef broth with egg custard

Third course: sole poached in Champagne with white sauce

Fourth course: roast pheasant with bread sauce and seasonal vegetables

Fifth course: filet of beef with truffle sauce

Sixth course: asparagus with hollandaise

Seventh course: a selection of cheeses, including Stilton and Cheddar

Eighth course: raspberry Charlotte Russe

Final course: fresh fruits and nuts

Each course was paired with a specific wine, and the host’s wine selection was as much a status symbol as the meal itself.

French wines were considered the height of sophistication, and a well-stocked cellar would include Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Sauternes. Port, Madeira, and vintage Champagne were also staples of aristocratic entertaining.

Seating and social rules

The seating arrangement at a formal dinner was carefully considered.

The host and hostess sat at opposite ends of the table, with the most distinguished guests placed nearest to them.

Seating was arranged according to social rank, and a guest’s placement at the table signified their importance.

(The Gilded Age on HBO)

Unmarried women were often placed next to eligible men in the hope of encouraging courtships. Likewise, strategic seating could help forge business and political alliances.

For guests of lower rank, an invitation to a prestigious dinner was an opportunity to elevate their social standing, but only if they conducted themselves properly.

Proper etiquette governed every aspect of the meal.

It was considered rude to talk across the table, so guests conversed only with those seated to their left or right. A lady always spoke to the gentleman on her right during the first course before turning to the gentleman on her left for the next.

Ignoring a neighbour or failing to show interest in the conversation could be seen as a slight.

Every aspect of dining was governed by rules.

Napkins were placed on the lap, never tucked into the collar. Silverware was used from the outside in, with different forks, knives, and spoons designated for specific courses.

Touching food with one’s hands, with the exception of bread, was strictly forbidden.

(For more on Manner in the Edwardian Era, check out Driehaus Museum’s article with that exact title!)

After-dinner traditions

Once dinner was complete, the ladies retired to the drawing room for tea and conversation, while the gentlemen remained at the table for cigars and brandy.

This tradition reinforced the rigid gender roles of the time, with women expected to engage in light conversation while men discussed business, politics, and other matters deemed unsuitable for ladies.

After about an hour, the gentlemen rejoined the ladies, and the evening continued with music, parlor games, or lighthearted conversation before guests departed.

(The creator of Downton Abbey and The Gilded Age, Julian Fellowes, discusses what one of these parties would have been like in this great article!)

Social perils and dinner party disasters

Despite careful planning, not every dinner party went smoothly.

Guests who failed to adhere to the rules of etiquette could find themselves the subject of whispered gossip.

Arriving late was a serious offense, as was failing to properly acknowledge one’s hostess. Using the wrong fork or misjudging a wine pairing could mark a guest as unrefined.

A breach of conversational etiquette was equally damaging.

Dinner conversation was expected to be light and pleasant, focusing on travel, fashion, literature, and society news.

Bringing up politics or business at the wrong moment, or making an inappropriate joke, could cast a shadow over the evening.

A guest who drank too much wine or monopolised the conversation risked social disgrace.

The highest echelons of British society were small and interconnected, and a single mistake could have lasting consequences.

A misstep at dinner might lead to fewer invitations or even outright exclusion from important social circles.

(However, these parties were wilder than we probably imagine! This fun article explains how and why.)

Hosting a Gilded Age-inspired dinner today

While the rigid etiquette of the Gilded Age has long faded, the grandeur of its dinner parties can still inspire modern entertaining.

Hosts today can recreate the elegance of the era by setting a beautifully arranged table with candlelight, serving a multi-course meal with thoughtful wine pairings, and encouraging guests to dress for the occasion.

Even small touches, such as a sorbet course or printed place cards, can add a touch of historical charm.

(At Mapperton, and at our home in London, I really like to use fun, mix-and-match plates and cutlery from charity shops!)

The Gilded Age dinner party was a carefully orchestrated display of wealth, culture, and power.

It was an opportunity to impress, to forge connections, and to reinforce social status.

While modern gatherings may be more relaxed, the spirit of these grand affairs lives on in the art of hospitality and the joy of a beautifully prepared meal.

(If you'd like some extra inspiration, check out Robert Dirk’s book, Food in the Gilded Age.)

Lovely to have these details, Julie. I write about a Cambridge ladies' dining club, and I wonder if it was started because these 12 women wanted to have a space to discuss serious issues (not just the rigidly defined lighter topics). Welcome to Substack!

Hi Julie! Love your articles. Found you on YouTube by accident and following the ups and downs you and Luke experience at Mapperton. You both handle things with grace, resilience, and persistence. When you have your formal dinners for guests it looks like you go all out to provide an experience somewhat like that of the gilded age Thank you for sharing!