The Life of Gilded Age Servants

Linens, loyalties, and long hours

We often think of the Gilded Age in terms of grandeur: the marble staircases, chandelier-lit ballrooms, and glittering soirées that played out in the drawing rooms of America’s and Britain’s wealthiest families. But beneath the gilt and glamour were the people who kept it all running, the maids, butlers, cooks, and footmen, whose labour sustained the illusion of effortless elegance.

From Fifth Avenue mansions to English country houses, these servants worked tirelessly, and often invisibly, to maintain the worlds of the famous faces still remembered today. While their employers changed for luncheons, social calls and garden parties, servants scrubbed, starched, and stood silently in the background, expected to anticipate needs, suppress their own, and remain unwaveringly loyal…

But what did life truly look like for those working below stairs in a Gilded Age household?

A world below stairs

In many Gilded Age households, the number of domestic servants often outnumbered family members. In Newport’s grand summer ‘cottages’ (mansions to us average Joes), it wasn’t uncommon for a household to employ 20 or more full-time staff during the season. In Britain, sprawling estates like Highclere or Waddesdon Manor had dozens more, all meticulously structured in hierarchy.

At the top sat the butler, who managed the wine cellar, silver, and male staff, while the housekeeper held equal authority over the female servants. Below them came footmen, lady’s maids, valets, cooks, kitchen maids, scullery maids, laundresses, chambermaids, hall boys, and more.

Each role was tightly defined. Footmen were prized not just for their service, but for their appearance, too, with tall, well-turned-out men who lent grandeur to the dining room preferred. Lady’s maids oversaw their mistress’s wardrobe and toilette, while scullery maids, as the youngest and lowest-ranking female servants, started their day before dawn, washing pots and lighting kitchen fires. Days could easily stretch 14 to 18 hours, with few breaks and even fewer days off.

According to the 1881 UK census, 1.6 million women in Britain were employed in domestic service, making it the largest category of female employment in the country.

In the United States, Irish women comprised the majority of domestic workers in northeastern cities such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, often entering service shortly after arriving through Ellis Island. German immigrants were more commonly found in domestic roles across the Midwest, while Chinese and Japanese servants were concentrated on the West Coast. In the South, African Americans, particularly women, formed the backbone of domestic labour, often having little choice but to continue a legacy of servitude in the post-emancipation era.

Linens and labour

One of the most critical duties in a Gilded Age household was maintaining the linen. The sheer volume was staggering: napkins, tablecloths, pillowcases, bed sheets, guest towels, and gown linings all had to be washed, dried, ironed, mended, and presented perfectly. Laundresses, often among the hardest-working and least visible staff, performed gruelling work amid heat, steam, and harsh chemicals.

A laundress’s working week ran from Monday through Saturday evening, with brief breaks throughout the day and Sundays off to rest. Laundering an average-sized household’s weekly linen could take days of labour. And with elite families changing outfits multiple times a day, the turnover was relentless.

Then came the servants’ hall, a central hub for all the domestic staff of the house and a social world unto itself. Although strictly hierarchical (at least in larger estates), with sections designated for different ‘ranks’ of domestic staff, it provided some sense of community. Here, meals were eaten, birthdays celebrated, romances, grievances and more played out quietly beneath the grandeur above.

Codes of conduct

For all their long hours and meagre wages, domestic servants were expected to uphold exacting standards of behaviour. Discretion was paramount. Servants were discouraged, and sometimes even forbidden, from speaking unless spoken to, and personal opinions were never to be expressed in front of employers.

British households, in particular, enforced a rigid deference system. Servants stood at attention until dismissed, and a misplaced glance or overfamiliar tone could result in instant dismissal.

Wages varied by region and role. In Victorian Britain, a housemaid might earn £18–25 per year, while a butler could earn £50 or more. In the U.S., live-in maids could earn around $18–$25 per month, which included meals and lodging.

Loyalties and limitations

While some staff stayed in service for decades, becoming trusted fixtures in the household, others faced an unending cycle of short-term contracts, layoffs, or relocations. Loyalty was valued, but often not reciprocated in kind. A single mistake, breaking a dish, falling ill, or attracting scandal, could mean instant dismissal without reference.

For women, especially, domestic service could be both opportunity and entrapment. It provided room, board, and a steady wage, but also left little room for marriage, independence, or upward mobility.

Despite the rigid hierarchy and pressures of domestic service, however, some staff did manage to form long-lasting bonds with their employers. Lady’s maids and valets, who worked in close proximity to their mistresses and masters, often spent many years in service and became trusted confidantes. While the nature of their relationship was shaped by class and duty, these senior household roles occasionally blurred the lines between employer and personal ally, albeit always within strict social limits.

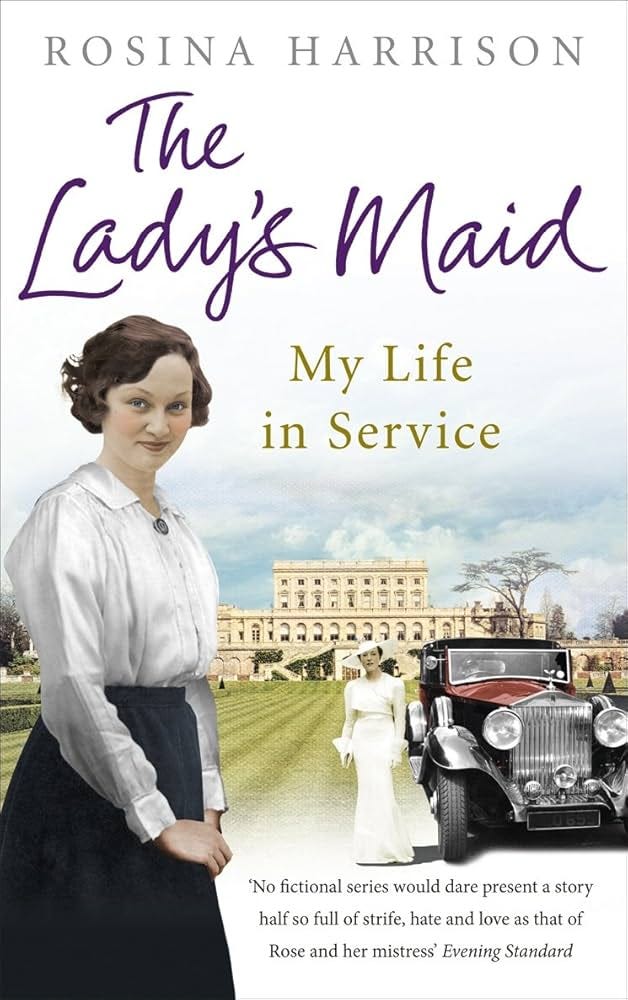

In her 1975 book, The Lady’s Maid: My Life in Service, Rosina Harrison describes a nuanced relationship with her mistress, the formidable Nancy Astor, showcasing how such roles could foster mutual respect over time (albeit with some perseverance…).

The shifting servant question

By the early 20th century, domestic service was already beginning to shift. The rise of labour-saving devices, changing social attitudes, and the effects of World War I caused a steep decline in the availability of live-in staff, particularly in Britain.

Former servants also began writing their own stories, and memoirs and oral histories revealed a more complex picture, one that included camaraderie between workers, indignities suffered, quiet rebellion, and pride in the craft of service.

Today, their legacy lives on not just in costume dramas, but in the very fabric of the homes they kept humming along.

For every silk gown smoothed, silver tray carried, and floorboards swept, there was a servant behind it. Their stories often went untold, tucked behind heavy double doors or lost in the shadow of their employers’ splendour.

But without them, the Gilded Age would have been far less gilded. They polished the surface that society admired, and in doing so, shaped the world we still romanticise today.

I've never thought about the cultural breakdown of domestic servants in America (even though I am American!) but it's interesting because the cultures you mention are still highly concentrated in those particular areas today.

Might just need to add the Harrison book to my shopping list...... thank you! Enjoyed your post...grew up watching Upstairs Downstairs on PBS.....