Health, Wealth and Hysteria: Wellness Culture in the Gilded Age

If you were a woman in the Gilded Age and felt a little faint, anxious or simply fed up with society’s demands, there was a ready diagnosis for your condition: hysteria.

Of course, the cure varied depending on your social standing. For some, it was a brisk walk and a tonic. For others, a trip to Switzerland, the latest physical therapies, or even a daily dab of cocaine.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ‘wellness’ was not merely a trend. For the rich, it was practically a lifestyle, one often prescribed by a doctor in a three-piece suit and reinforced by social expectation.

From steam baths in Baden-Baden to the therapeutic sea air of Scarborough, wellness culture was where medical fashion met genteel escapism. And for Gilded Age elites on both sides of the Atlantic, being unwell could be a statement as much as a condition.

The ‘delicate’ diagnosis

Physicians and society at large believed women were particularly prone to ill health and psychological disorders due to their biological weakness and reproductive cycles.

Thus, one of the most fashionable afflictions of the era was coined: ‘nervous exhaustion’. A vague condition believed to be brought on by too much mental stimulation, creativity, sexual impropriety, reading, or, worst of all, independent thinking.

Women who deviated from their expected roles were often diagnosed with the affliction, a catch-all term for symptoms that today might be labelled stress, depression, or burnout.

In Britain, rest cures were favoured. Women of means were prescribed near-total isolation, restricted diets and endless bed rest. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famous and incredibly haunting short story The Yellow Wallpaper was based on her own experience of this treatment. Unsurprisingly, the tale struck a nerve with many of her contemporaries.

Source: Author Charlotte Perkins Gilman, c. 1990, via Wikipedia.

In America, a more active approach to health was emerging, and those with deep pockets sought relief from their ailments in the mountains.

To the Alps for air and answers

Switzerland became the wellness destination of choice for wealthy Americans and Britons alike.

Sanatoria sprang up across Davos and Montreux, offering dry mountain air as the remedy for everything from tuberculosis to melancholy. At places like the Schatzalp in Davos, patients took in the fresh air, read approved literature, and spent their days reclining on loungers, wrapped in furs even in the height of summer.

Source: Women undertaking a regime of rest, c. 1900s, via Aspetar

These sanatoriums were more than medical centres. They were also seasonal retreats for the sick and the stylish. Sandwiched in between mandatory exercise classes and the latest therapies, one can imagine flirtations on the terrace and lively gossip in the drawing room, albeit whispered over coughs and hot milk.

Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel, The Magic Mountain, offers a fictionalised version of this world, inspired by his wife’s stay at a Davos sanatorium—an affiliation the hotel in question still uses to this day.

Well, you know what they say: there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

Source: A Davos Sanatorium in 1897. Via Medizinmuseum Davos.

Seaside cures and spa town chic

Closer to home, the British seaside was bustling with invalids.

Doctors prescribed sea air and cold bathing, thought to revitalise both body and mind. Towns like Brighton, Scarborough, and Torquay were filled with elegant ladies in bathing carriages, braving the bracing waters in pursuit of renewed vitality.

Meanwhile, spa towns such as Bath, Leamington Spa, and Buxton became hotspots for the upper crust seeking cure-all mineral waters. People drank litres of sulphuric water a day, soaked in thermal pools, and engaged in ‘taking the waters’ as much for the social scene as for the supposed health benefits.

Source: Leamington Spa, c. 1900s, via Mary Evans Picture Library.

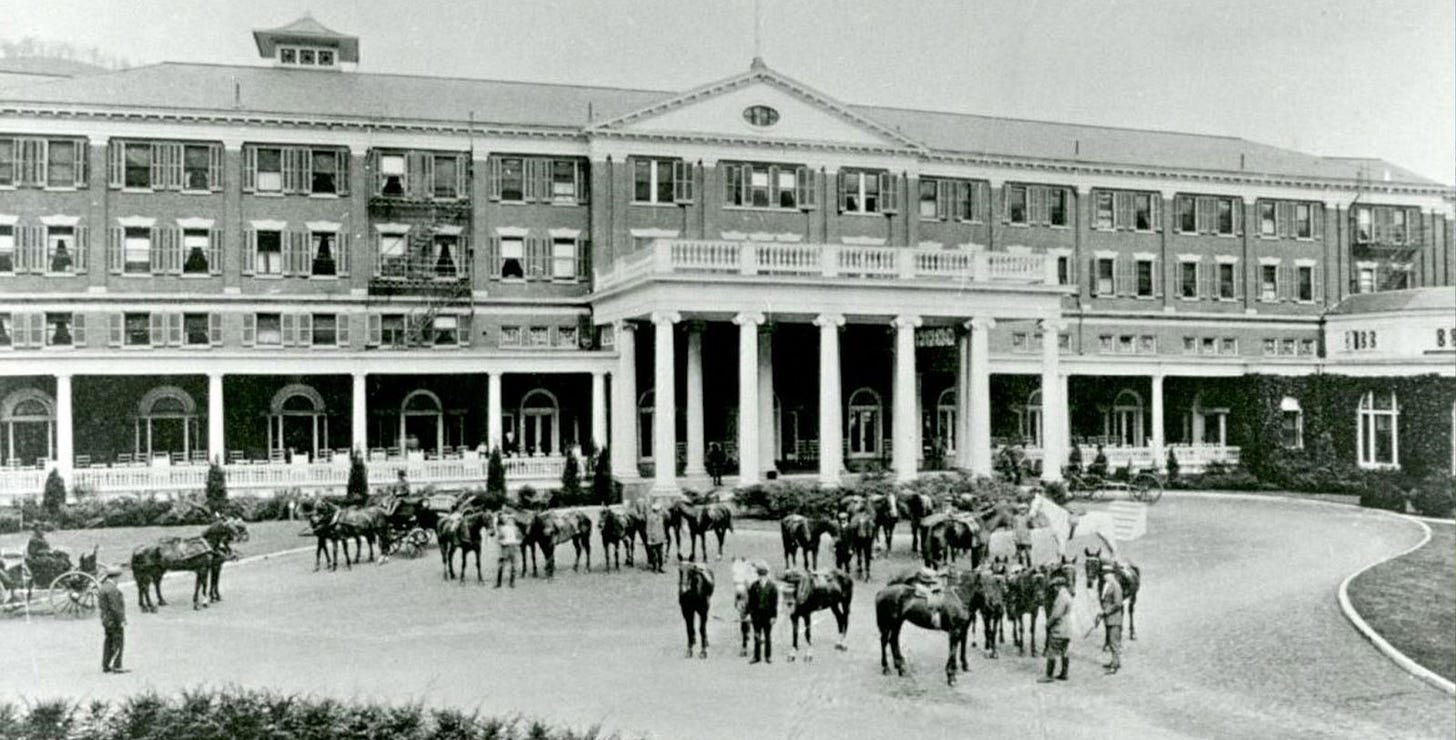

Over the pond in America, Saratoga Springs and Hot Springs, Virginia, played much the same role, offering mineral baths, fresh air and the possibility of socialising (not to mention the odd seasonal romance) while recuperating.

Source: The Omni Homestead Resort, c. 1900s, via Historic Hotels of America.

The rise of the wellness resort

By the turn of the century, the health resort had become a fully-fledged industry.

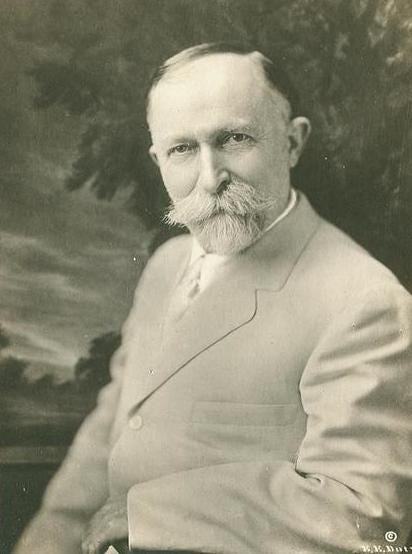

Places like Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan, founded by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (yes, that Kellogg, of the breakfast cereal), promoted strict vegetarian diets, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, hydrotherapy, electric baths, and even ‘mechanical massage’. High society flocked to these institutions, seeking both moral and physical purification.

Source: Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, c. 1915, via Wikipedia.

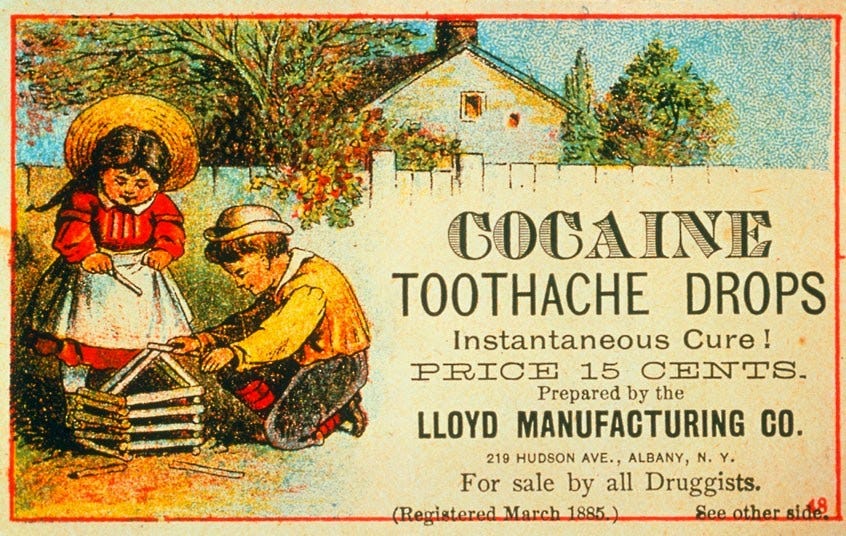

Fashionable ailments called for fashionable treatments. Cocaine was available in tinctures and lozenges for everything from toothache to eye and ear surgery, while morphine could be picked up over the counter. Even Queen Victoria’s doctor was rumoured to have prescribed cannabis oil for menstrual cramps.

Many of these remedies were promoted with aspirational and elegant marketing; their dangers, at best, largely unknown, and at worst, willfully ignored.

Source: Ad for medicinal drops to relieve toothache, Lloyd Manufacturing Co., 1885 via National Library of Medicine.

Hysteria as high drama

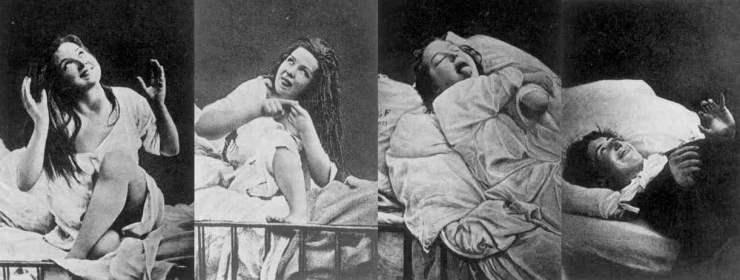

Hysteria in the Gilded Age was more than a diagnosis: it was a cultural, almost exclusively feminine identity.

The term was a one-size-fits-all label stuck to women for everything from religious obsession to childbirth, infidelity, tragedy, or even daring to ask for a divorce (something only the clinically insane would do, of course…). It was a means of controlling a subset of the population who defied societal norms and caused discomfort to those around them. And for some unlucky women, it was their one-way ticket to incarceration in an asylum.

Source: Women experiencing ‘hysteria’, c. 1870s, via Historic UK.

Despite this, the malady of hysteria could offer women, particularly those in the more restrictive middle and upper classes, a kind of sanctioned rebellion. An outlet, and the ability to express themselves without outright revolt in a society that frowned upon women’s emotional and intellectual autonomy.

Moreover, to be ‘delicate’ was to be seen. To suffer was to have purpose. And perhaps for heiresses caught between gilded expectations and a desire for self-expression, illness was the only socially acceptable means of escaping the confines of their standing.

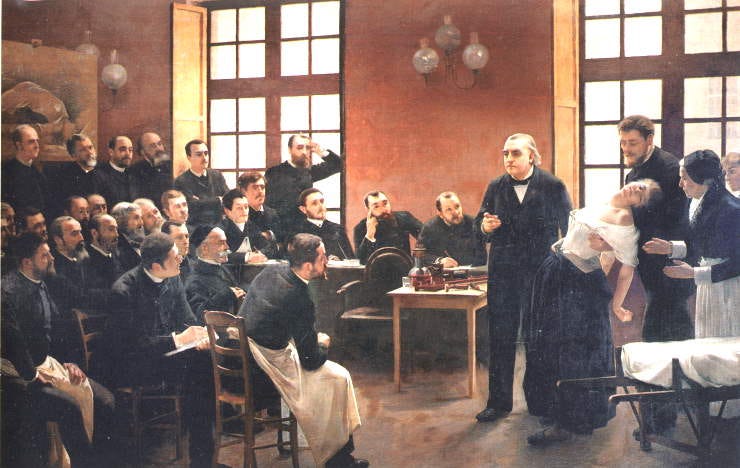

That’s not to say their suffering wasn’t real, however. But it was often filtered through the lens of class and gender, shaped by physicians who believed a woman’s uterus was the root of all distress—a belief traced back to ancient Greek medicine and, up until Freud changed the psychological landscape, a mainstay in diagnosis during the Victorian and Gilded Age eras.

Source: Painting of Jean Martin Charcot demonstrating hysteria, via Historic UK.

A fashionable façade?

Wellness in the Gilded Age sat somewhere between sincerity and spectacle. It was about health, yes, but it was also about status. A trip to Karlsbad or a cure in Davos was a mark of refinement. Carrying smelling salts, refusing strong sunlight, and sipping specially imported waters became part of the aesthetic of delicate femininity.

Like today, wellness was as much about the narrative as it was about health. And in the Gilded Age, that narrative was written in lace-trimmed journals, soaked in rosewater, and tucked inside a very fashionable medical bag.

Wealth allowed elite women to turn their ailments into rituals, and those rituals into routines that defined them. They may not have had yoga mats and green juice, but they had their own sacred rites, and they performed them in corsets.

The trope of the hysterical woman! It's a sticky one and still around, living under many guises!

A spa/resort vacation for stress issues sounds just about perfect in today’s society. Maybe one that bans screens.